Looking through the back door at twilight,

filaments of thorn rattle in the breeze like wire,

beyond a bare trestle scored with ice

dull shapes, then the vastness of night,

the hills, the mires, the barrelling sky,

and framing it, the outline

of the poet, faint as a phantom,

withering on the glass like a flame.

Monday, December 29, 2008

Wednesday, December 24, 2008

Christmas Story

People used to ask Nan MacDonald where she got the idea for her bet and she used to say ‘just a whim, a daft notion with a few pounds that’s all.’ She didn’t dare tell anyone the truth, not even her daughter Ruth, who probably wouldn’t have believed it anyway. Nan had never been one for betting but after she’d retired and she and Jock were trying to live on their pensions she had occasionally looked at the back pages of the Daily Record and thought about chancing her arm in one of these accumulator bets, a four horse yankee, or a football forecast or something like that. When she’d worked at McVitie’s in Dundee, the girls had often, daringly for the times, clubbed together for a flutter, sometimes put a bet on a whole race card, six bets in one. Jock had always frowned on the idea, though, told her it was a mug’s game and she’d be a pound better off at the end of the day if she didn’t bother. Jock had a bit of a puritanical streak- his father had been a Wee Free. Then Jock had caught Alzheimer’s, slowly at first but then with a sickening speed and his severity and his welcome and firm advice was no longer forthcoming. He began to talk disjointedly, or not at all for long periods of time, became peevish as a child and spent hours sitting in a chair staring out of the big attic window at the rooftops of Glasgow and the night sky.

They lived in a kirk hoose, sheltered accommodation run by the Church of Scotland and though Jock had got so bad that she knew he should be in a home, Nan did as much as possible to make his life comfortable, disguising when she could how difficult he had become, so they could both stay in the big flat they shared in Royal Circus and loved. Exhausted by her efforts, she didn’t give a thought to betting. She certainly thought more than once that it would be nice to have a wee bit extra, a couple of hundred pounds maybe to pay for a treat or luxury like the praline chocolates that Jock liked so much, but she reckoned that was an impossible dream. Then one day Jock had had come down from his armchair at the big window, come down with his strange shuffling walk, and said, matter–of-factly, ‘Dundee United to win the Scottish Cup 3-2 in injury time.’ This was strange: not only was it decisive and coherent in a way that Jock seldom was nowadays, but Nan knew for a fact that the Scottish Cup wasn’t even at the first round stage. She knew it because she followed football when she could, had done since the days her daddy used to take her to see Dundee play at Dens Park. She always followed the results from Dens Park and Tannadice, hoping, of course, that United lost.

‘What?’ she said, ‘what did you say Jock?’ But Jock had just sat down and was staring milky eyed at the TV as usual, oblivious to everything else. After a while she’d given up and returned to her knitting, a cardigan she was making for her little granddaughter Janet.

The next day Ruth had brought the wee girl round while Jock was having a bad spell, keeping trying to telephone his old work to say he wouldn’t be in till Monday week. She took the receiver from his hands for the seventh or eighth time and turned to her daughter.

‘He shouldn’t be here, Ma’ she said in a hard voice, ‘Ye’re no up to it. It’ll kill you.’

Nan shook her head. ‘Here we are and here we stay’, she had said cheerily. She was remembering her own mother’s voice rallying them after her daddy had been laid off from the docks. Here we are and here we stay.

‘Am no havin it, Ma’, Ruth had answered, unmoved. She had inherited the same steely resolve thought Nan, even as she was wishing she would be quiet and go away. ‘An going to go to the Social, Ma I am. You need to get this sorted.’ Her arms were folded and her foot was tapping on the lino. Janet was swaying on her wee feet beside her trying to do the same thing. Nan smiled in spite of herself.

‘Och Ruth things will be fine. You see if they’re not.’

‘I see they’re not now. Ye cannae manage him and this big place. Look at the state of you!”

Out of the corner of her eye she saw Jock reaching for the phone again. ‘Aye Jock’ she murmured, ‘phone for reinforcements’.

That night after he’d gone to bed, she was sitting in front of the fire sipping a small dram, half listening to Sportscene on the Telly, half mulling over what Ruth had said, when she head Dougie Donnelly say something like ‘…an easy cup win for the men from Tannadice over second division side Arbroath at Gayfield’ and then nearly jumped out of her skin because Jock was suddenly standing at her elbow shouting ‘GALWAY GIRL IRISH GRAND NATIONAL AT LEAPORDSTOWN 60-1 WINS BY EIGHT AND A HALF LENGTHS!’

After she’s put him back to his bed she rang Ruth’s. As she’d hoped, it was her son-in-law Fergus who had answered.

‘I’m doing a quiz’ she’d told him, ‘in one of the papers. When’s the Irish grand National run?’ ‘Sometime in May’ he’d answered in a puzzled voice, ‘a good bit yet anyway’. ‘Thanks very much’ said Nan and quietly but with great determination put down the phone and reached for her biro.

Two days later as she was taking Jock a walk in the park through the wet trees and the fractured February sunlight, he stopped and with great tenderness placed his hand on hers. It was the first time he had intentionally touched her for the best part of a year. She looked into his eyes and it was almost like looking at him again the way it had been walking out with him down the Seagate, him in his big scarf and her in her tartan muffler, the day she’d proposed to him. Jock pulled her head gently to his. ‘Jock, Jock,’ she whispered, ‘Jock, my love.’ A tear was trickling down his cheek, though the eyes were unblinking.

‘Rodger the Dodger,’ he whispered, and his voice was soft and smooth like a young man’s. ‘Rodger the Dodger in the Greyhound Derby. Comes from nowhere round the last bend.’ Nan put her head on his shoulder and wept.

Over the next ten days, with great care and precision, Jock made two other predictions, one when he was on the toilet and the other when he was shuffling round and round the settee in their living room. Plymouth Argyle would win the 4th Division Championship and Scotland would beat Brazil 1-0 in the World Cup. ‘Are you sure Jock?’ Nan had asked after a bit of research. ‘The Argyle are third bottom but I can still swallow that, but Scotland beat Brazil? Are you sure?’ Jock, as usual, had not answered, just dribbled a bit and Nan had carefully wiped his mouth with a napkin.

The day after, it was a Saturday, she had got Mrs Miraglees, the Matron of the Block to look after Jock for half an hour while she’d gone for a walk, and had gone into the Ladbrokes on Crow Road.

‘What can I do for you, love?’ a young man had asked. She had produced a sheet of writing paper from he handbag. ‘Could you quote me odds for these?’ she asked. ‘I want to put on a six-bet accumulator like we did at McVitie’s, the girls and I.’

The man frowned. ‘There are only five bets here,’ he said.

‘Indeed’ answered Nan, ‘I believe the last and greatest is yet to come.’

It took some time but when Nan hurried home she knew that the odds so far- on the accumulated five bets- were already forty thousand to one. When she got back she thanked the matron profusely. ‘I didn’t realise he was so bad’ the woman had said anxiously, ‘I really think we have to discuss things Nan’, Nan had hurried her to the door, settled Jock as best she could, then opened the third drawer of the bedroom cabinet. She took out a small enamel box and counted out the money she’d scrounged from their pensions and housekeeping over the last few years. It came to just over £251. She counted it out , feeling the folded notes in her fingers, thinking of all the times she’d nearly spent it on a wee bit of that, a little bit of this, and had drawn back. Clever girl, she thought, clever girl. It was what her Daddy had said when she brought home her first pay packet from the factory. Clever wee girl.

Over the next few weeks she waited and Jock had got worse and worse. He’s taken to shouting, frightening the other residents and had looked more than once in his frustration and confusion as if he was going to hit out, slap her with one of his big paws, but he hadn’t, he couldn’t. Jock was a gentle as a baby. Mrs Miraglee had rung the Social Services and so had the Home Help who Jock had sworn at, and they’d been to Ruth who’d given her tuppence worth, and the outcome of it all was that they had to be assessed, assessment being some fancy euphemism for incarceration and there was no way Jock was going to be locked up, he who had fought the Africa Korps and gone into battle with Nan’s letters bound by red ribbon in his breast pocket.

‘Come on, Jock’ she had said, ‘what is it? Tell me, it’ll set us free, but he had kept quiet though his head was shaking and the veins in his temple stood out as though some giant battle was being acted out inside. Then the day before the assessment, in the midst of twitching and groaning, he had rushed upstairs and she had followed, and he had looked out the big window over the city and had said, calm for a moment, ‘Aliens will land on Glasgow Green on Christmas Day.’

When he was fitfully asleep she had got one of the most good natured neighbours to step in for a moment and had nipped out, though nipped was not the word as she was so tired she could only just drag herself through the puddles. The bookie, after finding out she was serious, had to make calls to head office but emerged eventually to say ‘50,000 to 1 on that bet, dear’. She carefully unrolled the money, and completed the form. ‘Good luck’ the man had said, gravely, as she took the receipt.

Over the next few months when she visited Jock in the home as she did every day, in spite of the fact she had to change buses twice and her own health was failing, she had given him the good news. Galway Girl by a mile, Rodger the Dodger from nowhere, Dundee United in injury time, Plymouth Argyle on goal difference. They’d even watched the TV together in the residents’ lounge as, after Brazil had hit the woodwork eight times and had two goals controversially ruled offside, their goalkeeper unaccountably threw the ball into his own net on the stroke of full time.

Jock seemed to take nothing in. He was fading, really fading, his skin was turning transparent as if he would disappear. His breath was shallow, his eyes blank or filled with sudden, silent panic. The home was nice enough but it had few windows, certainly none to match the one in the attic at home, so on Christmas Eve, while she was pushing Jock in his chair through the grounds she had hurried him to a taxi, driven home and got the man to help take Jock up the stairs. She’d locked the doors and while Mrs Miraglee knocked and knocked, she’d held him in his old chair, one of the few pieces of furniture still unpacked in preparation for her leaving, and they had both stared at the darkening sky while she stroked his forehead as she used to and they waited, thinking each light in the sky was the light, the light of their love, come over the towers of the University and all the grey gutterings of Glasgow, to restore them.

Thursday, December 11, 2008

Little Girls Dream of the Snow

Though it never comes

except in stories,

their forecasting is assured,

as precise as orbits.

There will be snow.

They feel it,

they have heard whispers,

read signs buried in the sky,

when they wake up

the village will be gleaming,

cold and buried.

The BBC thinks otherwise

but satellites know nothing,

they have no faith,

there is no magic in their eyes.

Tomorrow we will be

reborn to a world both

beautiful and blind.

Sunday, December 07, 2008

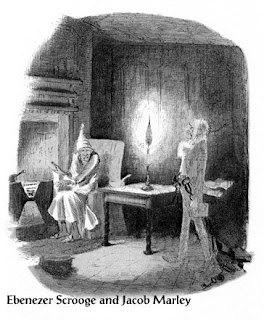

The Ghost of.....

Christmas again...with snow and black ice and lists to put up the chimney. The weans have their own ideas but I have my my own christmas rituals and memories. One was the little savings card my mother used to collect 3d a week to buy my Christmas present. I've still got it. One was a great romantic moment: A kiss from the most beautiful girl I knew, and the girl I loved dearly and in vain for many years, at the top of St Michaels' St in Dumfries- she ran, even, through the snow, leaving big footprints I went out to see the next day, just to make sure they were real. I can see her now, her hair and her smile,though she's long gone. Winter's a funny time; the dead seem closer than ever. What you remember, what you imagine, seems more real when the nights are long and black and icy. Didn't the Gaels call it the Thin Season when the gap between the dead and living was most thin,most penetrable?

I always read A Christmas Carol, the most beautiful Xmas story ever.

"Marley was dead, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. the register of his burial was signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker, and the chief mourner. Scrooge signed it. And Scrooge's name was good upon 'Change for anything he chose to put his name to. Old Marley was as dead as a door nail."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)